“[The minute that David] starts talking you realize you’re listening to someone highly intelligent, well-read and thoughtful. He had the audience in the palm of his hand. He’s perfect onstage interview. He chatted and answered questions for over an hour, and it could easily have gone on longer. Folks rushed to meet him and buy his books afterwards.” — Lewisburg Literary Festival, 2025

“[The minute that David] starts talking you realize you’re listening to someone highly intelligent, well-read and thoughtful. He had the audience in the palm of his hand. He’s perfect onstage interview. He chatted and answered questions for over an hour, and it could easily have gone on longer. Folks rushed to meet him and buy his books afterwards.” — Lewisburg Literary Festival, 2025

“Mr. Joy was a delight to work with from the first phone call up to his presentation. His storytelling and genuine approach are truly endearing. Not only that, but his writing is both relevant and authentically captures the essence of this region (Appalachia).” — Western Carolina University, 2025

“Mr. Joy was a delight to work with from the first phone call up to his presentation. His storytelling and genuine approach are truly endearing. Not only that, but his writing is both relevant and authentically captures the essence of this region (Appalachia).” — Western Carolina University, 2025

“David Joy absolutely charmed the audience at our Southern Author Fest panels. He has a knack for staying grounded and relatable while responding eloquently to questions and remarks by his fellow panelists. This man knows how to turn a phrase. We already have ideas for how we can invite him back. He is welcome anytime.” — Greenville County Library System, 2025

“David Joy absolutely charmed the audience at our Southern Author Fest panels. He has a knack for staying grounded and relatable while responding eloquently to questions and remarks by his fellow panelists. This man knows how to turn a phrase. We already have ideas for how we can invite him back. He is welcome anytime.” — Greenville County Library System, 2025

“David Joy lectured at the Alma MFA’s 2025 winter residency in Lake Junaluska, North Carolina, and also served as our degree ceremony speaker. The students and faculty couldn’t stop talking about him. He demonstrated what it means to live a truly authentic life, and to write with intention from that authenticity. They felt challenged to find their own way to live and write from such a powerful foundation. He spoke lovingly of growing up in the mountains of North Carolina, and why the location plays such an important role in his work, even when he’s telling difficult stories. I highly recommend David for any community looking to engage in conversations that will inspire and enlighten. He’s a sweet, funny presence (yes, you’ll laugh a lot!) who will bring a beautiful energy to any room.” — Sophfronia Scott, Director, Alma MFA in Creative Writing, 2025

“David Joy lectured at the Alma MFA’s 2025 winter residency in Lake Junaluska, North Carolina, and also served as our degree ceremony speaker. The students and faculty couldn’t stop talking about him. He demonstrated what it means to live a truly authentic life, and to write with intention from that authenticity. They felt challenged to find their own way to live and write from such a powerful foundation. He spoke lovingly of growing up in the mountains of North Carolina, and why the location plays such an important role in his work, even when he’s telling difficult stories. I highly recommend David for any community looking to engage in conversations that will inspire and enlighten. He’s a sweet, funny presence (yes, you’ll laugh a lot!) who will bring a beautiful energy to any room.” — Sophfronia Scott, Director, Alma MFA in Creative Writing, 2025

“Of the dozens of speakers I hosted over the seven years of a speaker series at the University of Delaware, David Joy is only one of two speakers I invited back. And if I had the opportunity, I would invite him back again! He provided thoughtful, genuine observations on topics related to race in America, Appalachia, politics, writing, and much more. He was as engaging in the classroom as he was at public events. He is, in many ways, a dream speaker because he actually listens to the questions and conversation being had, and thinks deeply when engaging in the dialogue. He is also funny, kind, and inspirational to be around.” — University of Delaware, 2024

“Of the dozens of speakers I hosted over the seven years of a speaker series at the University of Delaware, David Joy is only one of two speakers I invited back. And if I had the opportunity, I would invite him back again! He provided thoughtful, genuine observations on topics related to race in America, Appalachia, politics, writing, and much more. He was as engaging in the classroom as he was at public events. He is, in many ways, a dream speaker because he actually listens to the questions and conversation being had, and thinks deeply when engaging in the dialogue. He is also funny, kind, and inspirational to be around.” — University of Delaware, 2024

“[David] Joy writes like his hand was touched by God.” — The New York Times

“[David] Joy writes like his hand was touched by God.” — The New York Times

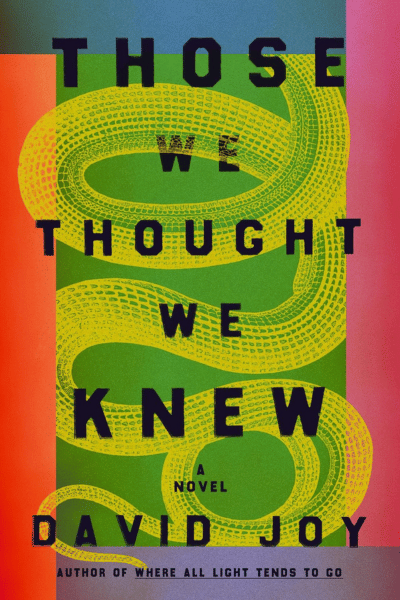

“Unflinching and timely…Joy has mastered the high-stakes, page-turning Appalachian-noir style, and through this lens, the preconceived notions of life in the mountains are overturned.” — Christian Science Monitor on Those We Thought We Knew

“Unflinching and timely…Joy has mastered the high-stakes, page-turning Appalachian-noir style, and through this lens, the preconceived notions of life in the mountains are overturned.” — Christian Science Monitor on Those We Thought We Knew

“Outstanding. . . When These Mountains Burn is a crime novel, surely – and a damn good one – but it’s also a snapshot of small-town America at a fracture point, when the least of the concerns is the fire that could consume everyone, all at once.” — USA Today on When These Mountains Burn

“Outstanding. . . When These Mountains Burn is a crime novel, surely – and a damn good one – but it’s also a snapshot of small-town America at a fracture point, when the least of the concerns is the fire that could consume everyone, all at once.” — USA Today on When These Mountains Burn

“A suspenseful page-turner, complete with one of the absolutely killer endings that have become one of Joy’s signatures.” — Los Angeles Times on The Line That Held Us

“A suspenseful page-turner, complete with one of the absolutely killer endings that have become one of Joy’s signatures.” — Los Angeles Times on The Line That Held Us

“Exquisitely written, heart-wrenching . . . Joy’s descriptions are lyrical and lingering.” — Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

“Exquisitely written, heart-wrenching . . . Joy’s descriptions are lyrical and lingering.” — Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

“David Joy’s novel brought me to my knees. Exquisitely written and heart-wrenching, it reminded me of Faulkner in its dark depiction of family loyalty — that “old fierce pull of blood.” . . . Joy’s descriptions are lyrical and lingering. . . . In the end, the line that holds Joy’s characters may be fraught and frayed, but its pull is fierce.” — Minneapolis Star Tribune

“David Joy’s novel brought me to my knees. Exquisitely written and heart-wrenching, it reminded me of Faulkner in its dark depiction of family loyalty — that “old fierce pull of blood.” . . . Joy’s descriptions are lyrical and lingering. . . . In the end, the line that holds Joy’s characters may be fraught and frayed, but its pull is fierce.” — Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Darkly stunning Appalachian noir.” — Huffington Post

“Darkly stunning Appalachian noir.” — Huffington Post

“[A] remarkable first novel . . . This isn’t your ordinary coming-of-age novel, but with his bone-cutting insights into these men and the region that bred them, Joy makes it an extraordinarily intimate experience.” — Marilyn Stasio, The New York Times Book Review on Where All Light Tends To Go

“[A] remarkable first novel . . . This isn’t your ordinary coming-of-age novel, but with his bone-cutting insights into these men and the region that bred them, Joy makes it an extraordinarily intimate experience.” — Marilyn Stasio, The New York Times Book Review on Where All Light Tends To Go